Seeing the Form

Line is the most fundamental element of iconographic representation. This however is not true of all painting traditions. For example, the Spanish Romanic painter Francisco Goya famously declared “Lines, always lines, I don’t see them in nature.”1 Goya was referring to outlines, which up until the Italian Renaissance were an important part of painted depiction. But no such outlines exist in our visual experience. Rather, as the art historian Frank Mather explains, “just the meeting of areas variously colored and lighted, contrasts of tone which the eye instantaneously interprets as form.”2 (See fig. 1). Outlines are a construct of the mind (νους—nous).

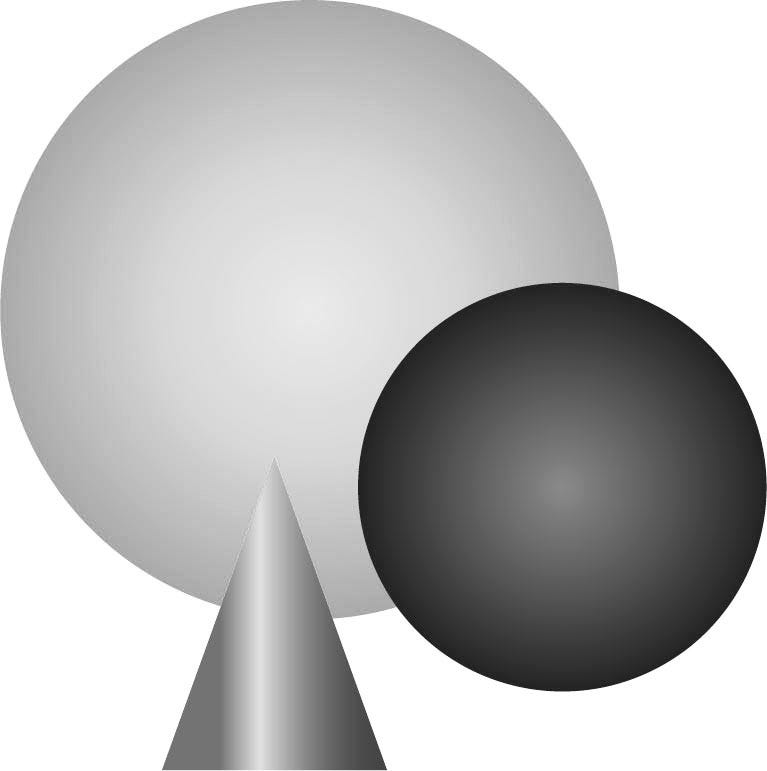

The ancients well understood this aspect of cognition. Indeed, for Aristotle, one visually perceives because the psyche or soul (today we would associate this with the brain, particularly the inferotemporal cortex) processes a jumble of sense-data through a matrix of relative relationships, locating each facet of what we see upon a spectrum of color or value and thus distinguishing things from other things. At the same time locating everything within a kind of relationship to everything else.3 This all takes place in a fraction of a second and produces a mental image (φάντασμα—phantasma) that presses itself upon the mind like a signet-ring upon clay or molten metal.4 The mind perceives in this particularized images form (μορφή— morphe). For, it is precisely form that makes one thing distinct from another. To use Aristotle’s vocabulary, form actualized matter.5 And he means this both metaphysically and in our perception or process of knowing the world.

Our senses apprehend the meeting of various areas of contrasting colors, brightness, and tones. But, what we see are in-formed objects. Subsequent philosophical and scientific exploration has only added more depth and nuance to this ancient description of human cognition. And it is this formal perception that has influenced the art of the icon which of course comes to us forms the Antique Hellenic world. Outline is a visual representation of what is most fundamental in human perception—form (see fig. 2).

For the artists of the Renaissance and the tradition that follows in their wake, these outlines needed to be abandoned for the artist to accurately render nature. This art is phantasmic; it seeks to re-present nature and trigger the process of formal cognition within the viewing subject.

It is important to note that this more naturalist approach to depiction was known in the ancient world, but was consciously abandoned by Late-Antique painters and the first Christian artists. For the ancients, this mimetic propensity of art was often looked upon which great suspicion. Artists, in their reproduction of nature, could and did “create” things that had no real existence. In other words, art could lie. Moralists and theorists in the Roman period were anxious about the inherent deceptiveness of illusionistic painting, and this deep suspicion was inherited by the early Christians. As the art historian, Jas Elsner explains,

naturalism—never the only mode of representation in the ancient world— became an untenable mode by late antiquity. In a culture which subjected the artifacts it produced to increasingly complex symbolic, exegetic and religious interpretations, art was expected to stand for symbolic and religious meanings rather than to imitate material things. Not only was the mimetic illusionism of naturalistic art no longer necessary to late-antique culture, but its very attempt to deceive was a barrier for those who sought truth or religious edification in images.6

Magnifying this aversion to artistic naturalism, early Christians saw in the hyper naturalism of ancient pagan religious depictions the most profound deception. Subsequently, the art of early Christianity, of which Byzantine iconography is a direct descendant, followed a different course to that of the illusionistic painting of ancient Greco-Roman culture.

This does not mean that naturalistic art is inherently idolatrous, nor are we making the claim that realistic painting is inherently antithetical to Orthodox Christian iconography, though many have argued as much.7 Only, that the art of the icon has a noetic rather than phantasmic character, for icons do not aim at illusionistic trompe-l'œil or a ‘fooling of the eyes.’Itdoesdirecttheeyes (or more accurately to the eyes of the mind) to divine personages, but in such a way that the depictions do not trigger the same kind of cognitive processes that material objects do. The image depicts but does not deceive.

Likewise theologically, they do not make a direct equation between the depiction and what is depicted.

Christ as God Made Visible

This last aspect of image theory, “how does an image relate to its prototype” become increasingly important in Patristic theology as the Church was tumultuously clarifying just how Jesus Christ is, in the words of St. Paul, “the image (εἰκὼν—eikon) of the invisible God” (Col. 3:15). What unfolded in this course of these controversies— particularly the Iconoclast Controversy that raged from the eighth to ninth centuries—was a gradated and nuanced spectrum of image relationships from ‘equation’ to ‘distinction.’ The distance that the icon both acknowledges and overcomes is deeply rooted in theology, not only the theology of the icon but in the larger sacramental theology and the Doctrine of the Incarnation upon which it rests.

As material and temporal beings, we know and encounter God, and can only know and encounter God, in a manner appropriate for us. This is the entire logic of Salvation History. For God did not reveal himself in abstract philosophical propositions but revealed (or more accurately restored) His image over time as His character came into greater relief and the contours of Covenantal Relationship became better inscribed. This shape of Salvation History is what allows us to see Christ as its culmination and the ultimate revelation and restoration of the image of God. Thus our “theology” or knowledge of God is, in the words of St. Theodore the Studite, indispensably dependent upon God’s “enter[ing] human nature and becom[ing] like us.”8 And as St. Gregory of Nyssa emphasizes, the Incarnation—the in-fleshing of God—is a “condescension to the weakness of human nature...changed to our shape (σχῆμά— schema) and form (ειδος—eidos).”9

For the Fathers, this real material and formal contact with God is far superior to merely conceptual knowledge which has no surety at arriving at the true knowledge of God. Our ideas or mental images can be just as idolatrous and disastrously erroneous as any idol made of wood or stone. Therefore, explains St. Maximus the Confessor in preferences to pretensious speculative theologizing, “there is that truly authentic knowledge, gained only by actual experience, apart from reason and ideas, which provides a total [sensual] perception of the known object through a participation by grace.”10 God reveals himself to us in his concealment and condescension in history culminating in the carnality and historicity of Jesus Christ. In St. Maximus’ extraordinary multivalent expression, the human nature of Jesus united to His divinity in the singleness of His Person, is the “οἰκείας ἐκφαντικὸς—a house of revelation, an economy of disclosure, or a dispensation of visibility.”11 The people of God can no longer say, we “saw no form” (Deut. 4:12). For the Israel of old did not see God, yet we are “with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord” (2 Cor. 3:18) shining in the face of Christ the very refulgence of the glory and exact imprint of the divine nature (cf. Heb. 1:3). “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9).

This divine visibility extends not just to His historical sojourn as if God incarnate in Christ had put off His temporally and historicity in the Resurrection and Ascension. This would be a dissolving of the Incarnation which had as St. John puts it, “filled” matter “with His grace and power.”12 No. In these events that same saving humanity became perpetually present in the sacramental Mysteries of the Church. “Do not cling to me” (John 20:17, also cf. 2 Cor.5:16) Christ tells the myrrh-bearing women after His Resurrection; because His risen flesh had not yet taken its place at the right hand of the Father. The nascent Church, concentrated in those women in the garden, was forbidden to cling to Christ’s mealy temporal presence in preference to a super-temporal tangibility that would come after the Ascension and through the dispensation of the Spirit: a tangibility that characterizes the life of the Church and our experience of the Lord. Incarnation is unto communion.

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life—the life was made manifest, and we have seen it, and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and was made manifest to us—that which we have seen and heard we proclaim also to you, so that you too may have fellowship [κοινωνίαν—koinonian, ‘communion’] with us; and indeed our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ. (I John 1:1-3)

The Church is the Body of Christ, the extension and manifestation of His redeemed and redemptive humanity. To be that place of saving encounter, to be truly redemptive for men, His presence is never without material, visible, tangible realization. Thus St. Leo PopeofRome puts it, “what was visible of our Redeemer is in sacramenta transivit—passed over into the Sacraments.”13 This is what is meant by the term οἰκονομια (oikonomia) or 'divine economy' which means at once both Salvation History and Sacramental structure and practice of the Body of Christ. In the light of faith (cf. Matt. 16:17) we can behold His incarnate flesh and recognize the Divine Lord (cf. John 20:28). The historicity of the God-Man and the materiality of the liturgical- sacrament are indispensably linked, Salvation History and the sacramental economy form but a single oikonomia.

By entering into time/space, God inaugurated a whole economy or dispensation of visibility. We encounter God in the Church via in-formed and deified matter in real space and time. The clearest example of this is the bread and wine of the Eucharist which is what it signifies (cf. 1 Cor. 11:23-29, Matt. 26:20-30, Mark 14:17-26, & Luke 22:14-23). Baptism likewise, doesn’t just signify a cleansing but does what it signifies, namely incorporates the believer into the new and risen humanity of Christ (cf. 1 Pet. 3:21-22 & Rom. 6:3-4). Icons participate in this economy of visibility and contact. As St. John of Damascus authoritatively affirms:

Fleshly nature was not lost when it became part of the Godhead, but as the Word made flesh remained the Word, so also flesh became the Word, yet remained flesh, being united to the person of the Word. Therefore, I boldly draw an image of the invisible God, not as invisible, but as having become visible for our sake by partaking of flesh and blood.14

***

It is obvious that when you contemplate God becoming man, then you may depict Him clothed in human form. When the invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw His likeness. When He who is bodiless and without form, immeasurable in the boundlessness of His own nature, existing in the form of God, empties Himself and takes the form of a servant in substance and in stature and is found in a body of flesh, then you may draw His image and show it to anyone willing to gaze upon it. Depict His wonderful condescension.15

***

I make an image of the God whom I see.16

But this mode of ‘visibility’ is rather distinct from the image-hood of Christ or the direct manifestation of the activity of Christ witnessed in the sacramental Mysteries.

In contrast to the sacraments, the icon simply serves to bring to the mind of the viewer those persons and realities represented. As St. Theodore explains, icons are “entirely different” than the material of the Eucharist, “for they are not the deified flesh, but” mediate a divine presence “by a relative participation” like a shadow pointing to its prototype.17 The matter of the icon is not itself divinized or divine, thus it only brings to the viewer a form that points to what it signifies. Sacred art is sacred, but its material mediation is indirect.

Thus, as St. Theodore draws out, Christ’s flesh, because it is the flesh of God, is worshiped (λατρεία—latreia), but the acts of reverence shown an icon (προσκύνησις— proskynesis, literally ‘prostration before’) is only veneration (δουλεία—douleia).18 For, any reverence given to the icon is not given to the mere wood, plaster, and paint, but according to the traditional axiom: “The honor given to the image passes over to the prototype.”19

Though indirectly mediating the Divine presence, the Church unequivocally defends and champions the iconographic tradition. Seeing encapsulated in it the whole doctrine of the Incarnation. As the historian of theology Jaroslav Pelikan explains, the Fathers of the Church who defended the images against the iconoclasts recognized that “the chronic heretical preference for a ‘heavenly body’...had now moved from the Gnostics to the iconoclasts, whose arrogant claim to be purely spiritual prompted them to disparage everything about Christ that was physical and visible.”20 Christ is divine and can be acknowledged as God, and likewise is fully man, so much so you can paint His portrait.

All of this theology informs the art of the icon both theoretically and in terms of the methods of depiction. Icons, experienced sensually by the viewer, are tasked with engendering divine encounter. Their manner of witnessing to the Incarnation is not one of strict imitation of divinized matter but rather a re-presentation of that Aristotelian intermediate space of formal cognition.

Both theoretically and theologically, the icon posits an implicit and self-conscious distinction between it and what it signifies and delineates this distance by its strong graphic character. The secondary place of naturalism in the art of the icon is due to this indirect mediation. For an eye attuned to western naturalism, icons may seem to be flat and two-dimensional. This is not quite intentional for icons do indeed convey three-dimensional figures. But, in a way utterly dependent upon form expressed visually as line.

Frank Jewett Mather, A History of Italian Painting (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1923), 131.

Mather, A History of Italian Painting, 131.

Aristotle, De Anima, 2. 12, A; 3. 2, 426b; 3.

De Anima, 2. 12, B.

Ibid. 2. 1, 412a.

Jaś Elsner, Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 18-19.

Cf. Michel Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002), 72-83. Mikhai Kasilin likewise addresses this position in detail in the context of the debate as it unfolded in pre-soviet Russia. Cf. "Chapter or Essay Title," in A History of Icon Painting: Sources, Traditions, Present Day, trans. Kate Cook, ed. L. Evseyeva (Moscow: Grand-Holding Publishers, 2002), 209-230. Also, cf. Irina Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, trans. P. Grenier (Brewster, Massachusetts: Paraclete Press, 2010), 39-42.

St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons, 1. 2.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Life of Moses, II. 28.

Maximus, Ad Thalassium, 60; quoted in Bissera V. Pentcheva, Hagia Sophia: Sound, Space, and Spirit in Byzantium (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 7.

Maximus, Ambigua to Thomas, 5.18.

John of Damascus, On Divine Images, 1; 16.

Leo, Serm. 74, On the Ascension, 2.

John of Damascus, On Divine Images, 1; 4.

On Divine Images, 1; 8.

On Divine Images, 1; 16.

Theodore, On the Holy Icons, 1. 12; also, cf. 2. 20.

This distinction is the central theme of St. Johns,' 'Third Apology' of On Divine Images, 3; 27- 42.

Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, 18. 45.

Jaroslav Pelikan. Imago Dei: The Byzantine Apology for Icons. The A.W. Mellon Lectures on

Fine Arts series XXXV:36 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 115.